Clinical trial replication stands as the cornerstone of modern medical science, transforming promising discoveries into trustworthy treatments that save millions of lives worldwide. 🔬

In an era where medical breakthroughs flood headlines daily, the scientific community faces a critical challenge: distinguishing between genuine therapeutic advances and fleeting statistical anomalies. While a single study might generate excitement, it’s the painstaking process of replicating findings across multiple trials that ultimately determines whether a treatment becomes standard care or fades into obscurity.

The replication crisis in science has exposed vulnerabilities in how medical research is conducted, published, and implemented. Understanding the power and necessity of clinical trial replication isn’t just an academic exercise—it’s fundamental to ensuring that patients receive safe, effective treatments backed by robust evidence rather than preliminary optimism.

🎯 Why Replication Matters More Than Initial Discovery

The journey from laboratory discovery to clinical application is fraught with complexity. Initial clinical trials, while exciting and hypothesis-generating, represent merely the first chapter in a much longer story. These preliminary studies often involve small sample sizes, specific populations, and controlled conditions that may not reflect real-world medical practice.

Replication serves multiple critical functions in the scientific method. First, it verifies that initial findings weren’t the result of chance, statistical manipulation, or unrecognized confounding variables. Second, it tests whether results hold true across diverse populations, geographic locations, and clinical settings. Third, replication studies often uncover side effects or limitations that smaller initial trials missed entirely.

Consider the pharmaceutical industry’s sobering statistics: approximately 90% of drugs entering clinical trials ultimately fail to reach market approval. Many of these failures occur precisely because initial promising results couldn’t be replicated in larger, more rigorous studies. This high attrition rate, while disappointing, actually demonstrates the system working as intended—protecting patients from ineffective or harmful treatments.

The Economic Impact of Failed Replication

Beyond patient safety, replication has enormous economic implications. Pharmaceutical companies invest billions of dollars in drug development, with estimates suggesting it costs approximately $2.6 billion to bring a single new medication to market. When early-stage results fail to replicate, these investments evaporate, driving up costs for successful drugs and ultimately affecting healthcare affordability.

Healthcare systems worldwide also bear costs when implementing treatments based on non-replicable research. Hospitals purchase equipment, train staff, and restructure protocols around new therapies. If these interventions later prove ineffective, resources have been diverted from potentially more beneficial applications.

📊 The Anatomy of Robust Clinical Trial Replication

Effective replication isn’t simply about repeating an experiment verbatim. The most valuable replication studies strategically vary certain parameters while maintaining core methodology, testing the boundaries of a finding’s validity and applicability.

Strong replication studies typically incorporate several key elements:

- Larger sample sizes: Expanding participant numbers increases statistical power and reduces the likelihood that results reflect random variation rather than true effects.

- Diverse populations: Testing across different ages, ethnicities, geographic regions, and comorbidity profiles ensures treatments work broadly rather than in narrow subgroups.

- Independent research teams: When different investigators with no vested interest in confirming initial findings conduct studies, bias is minimized.

- Varied methodological approaches: Using slightly different protocols or measurement tools helps determine whether findings are robust or dependent on specific technical details.

- Longer follow-up periods: Extended observation reveals long-term efficacy and safety profiles that short initial trials cannot capture.

Phase Progression in Clinical Development

The clinical trial system inherently builds replication into its structure through sequential phases. Phase I trials establish basic safety in small groups. Phase II expands to larger cohorts testing efficacy signals. Phase III represents large-scale replication across hundreds or thousands of participants, often at multiple centers internationally. Post-marketing Phase IV studies continue monitoring in real-world populations, providing ongoing replication data.

This phased approach exemplifies systematic replication, with each stage building confidence through progressively larger and more diverse populations. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require this multi-phase evidence precisely because single studies, regardless of size, provide insufficient certainty for widespread clinical use.

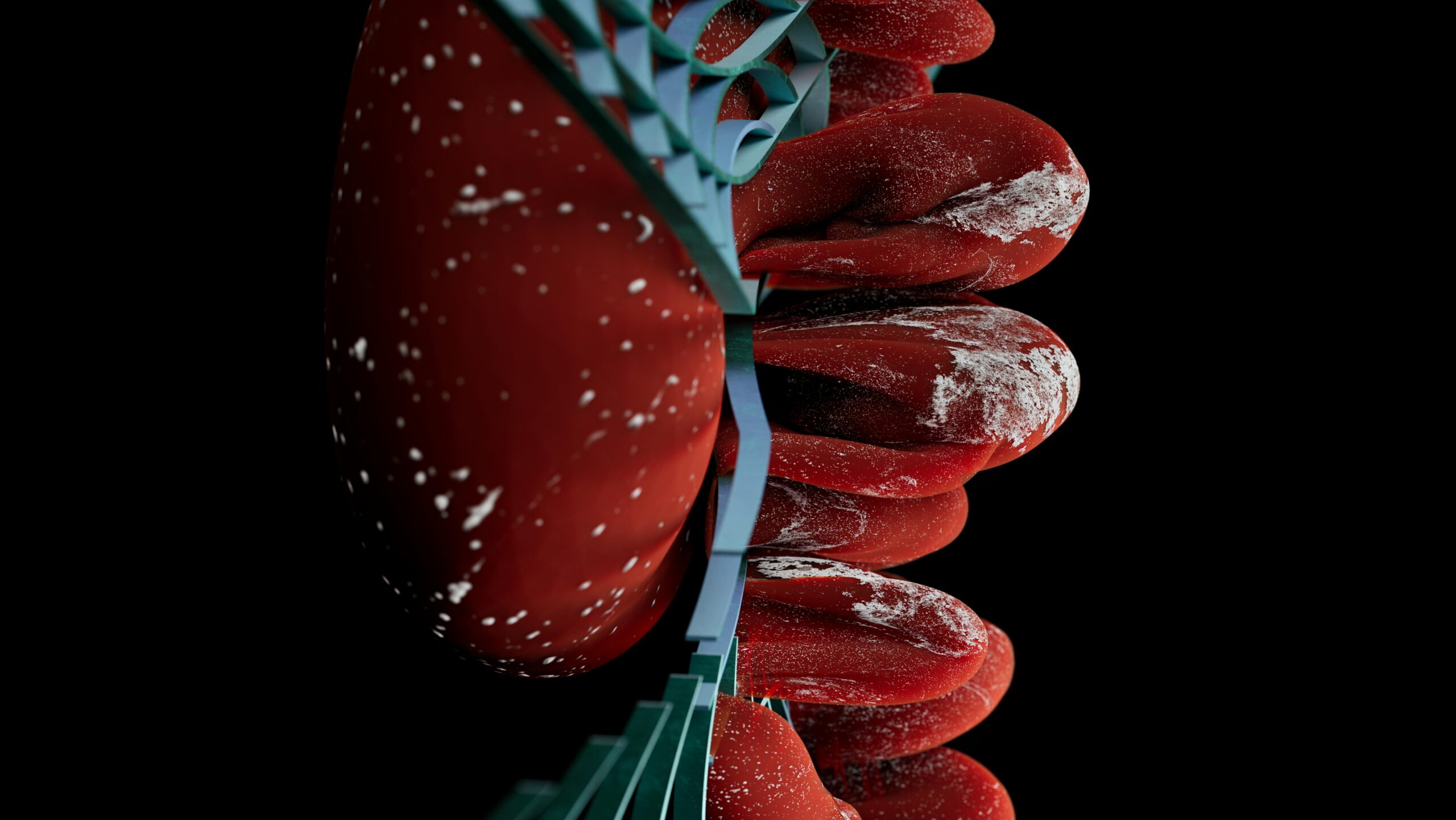

🧬 Landmark Cases: When Replication Changed Everything

Medical history offers numerous examples where replication either confirmed revolutionary treatments or exposed dangerous flaws in preliminary research. These cases illuminate why patience and scientific rigor ultimately serve patients better than rushing treatments to market.

The Hormone Replacement Therapy Reversal

For decades, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was widely prescribed for postmenopausal women based on observational studies suggesting cardiovascular benefits. However, when the Women’s Health Initiative conducted large randomized controlled trials—essentially replication studies with stronger methodology—they discovered HRT actually increased cardiovascular risks and breast cancer incidence. This replication effort prevented countless adverse outcomes and fundamentally changed clinical practice guidelines.

Checkpoint Inhibitors: Replication Validates a Revolution

Conversely, immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment demonstrated remarkable consistency across replication studies. Initial trials showing dramatic responses in melanoma were successfully replicated across multiple cancer types, diverse populations, and independent research centers. This consistent replication accelerated regulatory approval and established immunotherapy as a cornerstone of modern oncology, saving thousands of lives annually.

The Alzheimer’s Drug Pipeline Challenges

The Alzheimer’s disease field has experienced repeated failures when promising Phase II results couldn’t replicate in Phase III trials. Drugs targeting amyloid plaques showed encouraging preliminary data for years, but larger replication studies consistently failed to demonstrate meaningful clinical benefits. Only recently have some treatments shown replicable modest effects, highlighting how replication protects patients from ineffective therapies and guides research toward more promising mechanisms.

💡 Addressing the Replication Crisis in Medical Research

The broader scientific community has confronted a “replication crisis” where numerous published findings fail to replicate when independently tested. Medical research, with its direct implications for patient care, faces particularly high stakes in addressing this challenge.

Several factors contribute to replication failures in clinical research. Publication bias favors positive results, creating literature that overrepresents successful findings while negative or null results languish unpublished. P-hacking and data dredging—analyzing data multiple ways until statistically significant results emerge—produce false positives that won’t replicate. Small sample sizes in preliminary studies lack statistical power, making chance findings appear significant.

Solutions and Best Practices Emerging

The research community has responded with initiatives designed to improve replicability. Pre-registration of clinical trials, where researchers publicly commit to specific hypotheses and analysis plans before data collection, prevents post-hoc data manipulation. Open science practices, including data sharing and transparent methodology, enable independent verification and replication attempts.

Funding agencies increasingly support replication studies, recognizing their value despite lacking the novelty that traditionally attracts research dollars. Journals have begun publishing high-quality replication studies and negative results, correcting the publication bias that skewed medical literature toward false positives.

Statistical reforms also play crucial roles. Lowering p-value thresholds, emphasizing effect sizes and confidence intervals over binary significance testing, and requiring larger sample sizes all increase the likelihood that published findings will replicate successfully.

🌍 Global Collaboration: Amplifying Replication Power

Modern clinical trial replication increasingly leverages international collaboration, pooling resources and patient populations across borders to generate robust evidence more efficiently. Multi-center trials conducted simultaneously across countries provide built-in replication while accelerating timelines.

Organizations like the Cochrane Collaboration systematically review and synthesize evidence across multiple trials, essentially meta-analyzing replication attempts to generate comprehensive conclusions about treatment efficacy. These systematic reviews and meta-analyses represent the highest tier of evidence-based medicine, precisely because they aggregate replication data.

Technology Enabling Better Replication

Digital health technologies are revolutionizing how replication studies are conducted. Electronic health records enable large-scale observational studies that replicate trial findings in real-world populations. Wearable devices and smartphone applications facilitate remote monitoring, expanding trial participation beyond traditional research centers and enhancing population diversity.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning tools help identify patterns across multiple studies, detecting subtle replication failures or unexpected subgroup variations that human reviewers might miss. These technologies also streamline data harmonization across studies with different protocols, making meta-analyses more comprehensive and reliable.

⚖️ Balancing Speed and Certainty: Lessons from Recent History

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically illustrated tensions between rapid therapeutic development and thorough replication. Emergency use authorizations allowed vaccines and treatments to reach patients faster than traditional approval processes permit, based on less extensive replication than normally required.

This accelerated timeline produced remarkable successes—multiple effective vaccines developed in record time—but also highlighted risks. Some treatments initially showing promise in small studies failed to demonstrate efficacy in larger replication trials. Hydroxychloroquine, initially promoted based on limited preliminary data, ultimately proved ineffective in rigorous replication studies, demonstrating why even during emergencies, replication matters.

The pandemic experience taught valuable lessons about adaptive trial designs that build replication into accelerated timelines. Platform trials testing multiple interventions simultaneously, with interim analyses allowing early stopping for futility or efficacy, provide faster answers while maintaining scientific rigor through built-in replication mechanisms.

🔮 The Future of Clinical Trial Replication

Looking forward, clinical trial methodology continues evolving toward more efficient, robust replication processes. Pragmatic clinical trials conducted within routine healthcare settings test whether interventions work in real-world conditions, essentially replicating controlled trial findings in naturalistic environments.

Precision medicine approaches will require replication strategies that account for treatment heterogeneity. As therapies become increasingly targeted to specific genetic profiles or biomarker signatures, replication studies must verify that these precision approaches deliver promised benefits across the biological diversity within target populations.

Patient Engagement in the Replication Process

Patient advocacy groups increasingly recognize replication’s importance and actively participate in research prioritization. When communities affected by specific diseases understand that replication protects them from ineffective treatments while validating genuine breakthroughs, they become powerful allies in promoting rigorous science over premature enthusiasm.

Patient registries and networks facilitate replication by maintaining contact with willing research participants across studies, reducing recruitment challenges that often delay or prevent replication attempts. This infrastructure strengthens the entire clinical research ecosystem.

📈 Measuring Success: What Good Replication Looks Like

Successful replication doesn’t always mean obtaining identical results to initial studies. Effect sizes may vary across populations or settings while still confirming the underlying therapeutic principle. Understanding this nuance prevents dismissing valuable replication data that shows modest variation from original findings.

Meta-epidemiological research examines patterns across replication attempts, identifying factors that predict which findings will replicate successfully. Initial effect sizes, sample sizes, study design rigor, and biological plausibility all influence replication likelihood. These predictive models help prioritize which preliminary findings merit substantial investment in replication efforts.

| Factor | High Replication Likelihood | Low Replication Likelihood |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Sample Size | Large (>1000 participants) | Small (<100 participants) |

| Effect Size | Moderate, biologically plausible | Extremely large or implausibly perfect |

| Study Design | Randomized, controlled, blinded | Observational, uncontrolled |

| Mechanism | Clear biological rationale | Unclear or speculative mechanism |

| Pre-registration | Hypotheses and analyses pre-specified | Exploratory, post-hoc analyses |

🎓 Educating Stakeholders About Replication’s Value

Broader understanding of replication’s crucial role requires education across multiple stakeholder groups. Medical professionals need training in critically appraising evidence, recognizing that single studies—regardless of publication venue—provide insufficient basis for changing practice. Policymakers must understand why rushed approvals based on inadequate replication can harm public health despite political pressure for rapid action.

Media coverage of medical research often sensationalizes preliminary findings without emphasizing replication’s necessity. Improving science communication to highlight when findings represent early-stage hypotheses versus replicated, practice-changing evidence would help public understanding and reduce premature adoption of unproven interventions.

Academic incentive structures traditionally rewarded novel discoveries over replication studies, creating disincentives for researchers to conduct essential but less glamorous confirmation work. Reforming promotion and tenure criteria to value high-quality replication alongside original discoveries would strengthen the entire research enterprise.

🌟 Building a Culture That Values Scientific Rigor

Ultimately, unlocking medical breakthroughs through robust replication requires cultural change across the research ecosystem. This means celebrating null results that spare patients from ineffective treatments as enthusiastically as positive findings. It means recognizing that science advances through incremental confirmation rather than revolutionary leaps alone.

The most transformative medical advances—antibiotics, vaccines, cancer immunotherapy, antiviral medications—all succeeded because their benefits replicated consistently across diverse studies and populations. Their reliability, established through extensive replication, enables physicians to prescribe with confidence and patients to trust their treatments.

As precision medicine, gene therapy, and other cutting-edge modalities emerge, the fundamental principles of replication remain unchanged. Before declaring victory over disease, we must confirm that treatments work consistently, safely, and effectively across the populations who need them most.

The power of clinical trial replication lies not in dampening enthusiasm for discovery but in ensuring that enthusiasm translates into genuine therapeutic advances rather than false hope. By demanding robust replication before widespread implementation, we honor both the scientific method and our obligations to patients who trust medical science to improve their lives. This commitment to rigor, though sometimes slowing immediate gratification, ultimately accelerates true progress by building on foundations of reliable, reproducible evidence that transforms medicine for generations to come. ✨

Toni Santos is a health systems analyst and methodological researcher specializing in the study of diagnostic precision, evidence synthesis protocols, and the structural delays embedded in public health infrastructure. Through an interdisciplinary and data-focused lens, Toni investigates how scientific evidence is measured, interpreted, and translated into policy — across institutions, funding cycles, and consensus-building processes. His work is grounded in a fascination with measurement not only as technical capacity, but as carriers of hidden assumptions. From unvalidated diagnostic thresholds to consensus gaps and resource allocation bias, Toni uncovers the structural and systemic barriers through which evidence struggles to influence health outcomes at scale. With a background in epidemiological methods and health policy analysis, Toni blends quantitative critique with institutional research to reveal how uncertainty is managed, consensus is delayed, and funding priorities encode scientific direction. As the creative mind behind Trivexono, Toni curates methodological analyses, evidence synthesis critiques, and policy interpretations that illuminate the systemic tensions between research production, medical agreement, and public health implementation. His work is a tribute to: The invisible constraints of Measurement Limitations in Diagnostics The slow mechanisms of Medical Consensus Formation and Delay The structural inertia of Public Health Adoption Delays The directional influence of Research Funding Patterns and Priorities Whether you're a health researcher, policy analyst, or curious observer of how science becomes practice, Toni invites you to explore the hidden mechanisms of evidence translation — one study, one guideline, one decision at a time.