Environmental interference factors silently shape every aspect of our existence, from the air we breathe to the technologies we depend on daily. 🌍

In an increasingly interconnected world, understanding how environmental disruptions influence our lives has never been more critical. These hidden disruptors operate across multiple dimensions—physical, biological, technological, and social—creating ripple effects that extend far beyond their immediate impact zones. As we advance into an era defined by climate change, urbanization, and technological dependence, recognizing and addressing these interference factors becomes essential for securing a sustainable future.

The Invisible Architecture of Environmental Disruption

Environmental interference factors represent a complex web of interactions that disrupt natural systems, human activities, and technological infrastructure. Unlike obvious environmental challenges such as pollution or deforestation, these disruptors often operate beneath the surface of our awareness, manifesting through subtle but cumulative effects that reshape our world over time.

These interference patterns emerge from multiple sources: electromagnetic radiation from our wireless devices, chemical compounds released into ecosystems, acoustic pollution in urban environments, and even the thermal signatures of our built environments. Each factor independently may seem insignificant, but collectively they create a phenomenon scientists call the “interference cascade”—where multiple small disruptions combine to produce disproportionately large consequences.

Electromagnetic Interference: The Digital Age’s Silent Footprint

Our modern civilization runs on invisible waves of electromagnetic energy. Every smartphone, Wi-Fi router, satellite transmission, and power line generates electromagnetic fields that permeate our environment. While these technologies have revolutionized communication and commerce, they also create interference patterns that affect biological systems in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Research indicates that electromagnetic interference (EMI) affects not only sensitive electronic equipment but also natural navigation systems used by migratory birds, marine mammals, and insects. Bees, for instance, rely on Earth’s magnetic field for orientation—a system that can be disrupted by strong electromagnetic sources near their hives. This biological interference has implications for pollination patterns, agricultural productivity, and ecosystem health.

For human populations, the debate continues about potential health effects of prolonged electromagnetic exposure. While conclusive evidence remains elusive, precautionary approaches have gained traction in urban planning and technology design. Smart cities now incorporate EMI mapping into their development strategies, identifying interference hotspots and implementing mitigation measures. ⚡

Chemical Interference: The Molecular Disruption of Natural Systems

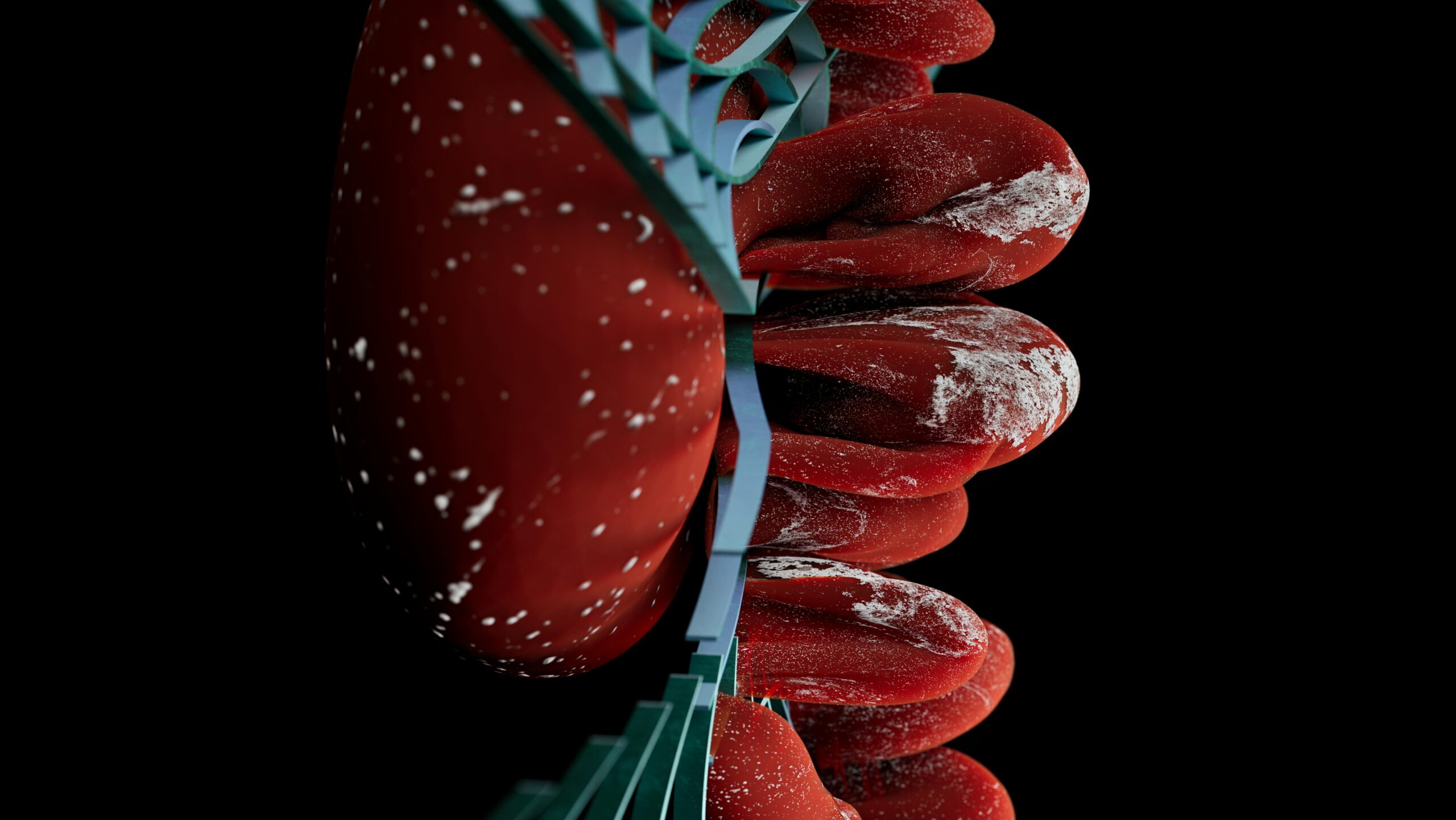

Perhaps no category of environmental interference has received more attention than chemical pollutants. Yet the conversation has evolved beyond traditional pollutants like heavy metals and pesticides to encompass a new generation of disruptors: microplastics, endocrine-disrupting compounds, and pharmaceutical residues that alter biological processes at microscopic levels.

These substances interfere with natural systems through multiple pathways. Endocrine disruptors mimic hormones, confusing biological signaling systems in wildlife and humans alike. Microplastics provide surfaces for pathogenic bacteria to colonize, creating new disease transmission vectors. Pharmaceutical compounds excreted by humans and concentrated in wastewater create evolutionary pressure on bacteria, accelerating antibiotic resistance.

The Cascade Effect in Aquatic Ecosystems

Water systems serve as highways for chemical interference factors, transporting compounds across vast distances and concentrating them through biological processes. A single pharmaceutical factory’s discharge can affect river ecosystems hundreds of kilometers downstream, altering fish reproduction, immune function, and behavior patterns.

The interference doesn’t stop at biological boundaries. Chemical compounds affect physical processes too—surfactants from detergents alter water surface tension, affecting gas exchange rates between water and atmosphere. This seemingly minor interference cascades through food webs, ultimately affecting oxygen availability for aquatic organisms and the carbon cycle’s efficiency.

Acoustic Interference: When Silence Becomes Endangered 🔊

Sound pollution represents one of the most underappreciated environmental interference factors. Urban areas generate continuous acoustic backgrounds that mask natural sounds, disrupt animal communication, and affect human health through chronic stress responses. This interference extends far beyond cities—shipping noise penetrates ocean depths, mining operations create seismic disturbances, and air traffic generates sonic footprints across vast territories.

Marine mammals, which depend on acoustic signals for navigation, feeding, and social bonding, face particular challenges. Sonar systems, shipping traffic, and offshore construction create acoustic interference that can disorient whales, separate mothers from calves, and disrupt feeding behaviors. Mass strandings of marine mammals have been linked to naval sonar exercises, demonstrating the lethal potential of acoustic interference.

Terrestrial ecosystems face similar challenges. Birdsong serves essential functions in territorial defense and mate attraction, but urban noise forces birds to alter their vocalizations—singing at higher frequencies, increasing volume, or shifting to nighttime activity. These adaptations carry costs: higher-pitched songs may convey less information, louder singing requires more energy, and nocturnal activity exposes birds to different predators.

Thermal Interference: The Heat Signature of Civilization

Human activities generate enormous quantities of waste heat—from industrial processes, vehicles, buildings, and even our own bodies concentrated in cities. This thermal interference creates urban heat islands where temperatures can exceed surrounding rural areas by 5-10 degrees Celsius, fundamentally altering local climates and ecological processes.

These heat islands don’t simply make cities uncomfortable during summer; they reshape precipitation patterns, extend growing seasons for both crops and pests, and create thermal barriers that affect wildlife movement. Insects, being cold-blooded, show particular sensitivity to temperature changes, with urban heat islands accelerating their reproductive cycles and potentially altering disease transmission dynamics.

Industrial Thermal Pollution

Power plants and manufacturing facilities discharge heated water into rivers and coastal areas, creating thermal plumes that can extend for kilometers. This interference affects dissolved oxygen levels, accelerates chemical reaction rates, and creates thermal stress for aquatic organisms adapted to narrower temperature ranges. Some species cannot survive in thermally polluted areas, while others—often invasive or opportunistic species—thrive, reshaping ecological communities.

Light Interference: Erasing the Night Sky ✨

Artificial light at night represents a relatively recent environmental interference factor, but one with profound implications. Light pollution affects over 80% of the global population and 99% of Europeans and Americans, fundamentally altering natural light-dark cycles that evolved over billions of years.

This interference disrupts circadian rhythms in organisms ranging from microbes to humans. Plants exposed to artificial night lighting show altered flowering times, potentially creating mismatches with pollinator activity. Insects, attracted to artificial lights, exhaust themselves or become easy prey, with cascading effects on insectivorous species and pollination services. Sea turtle hatchlings, naturally drawn toward moonlight reflected on ocean waves, instead head toward coastal development lights, often with fatal consequences.

For humans, light interference affects melatonin production, sleep quality, and potentially cancer risk through disrupted circadian regulation. Urban dwellers rarely experience true darkness, with implications we’re only beginning to understand for mental health, metabolic function, and disease susceptibility.

Technological Convergence: When Interference Factors Multiply

Individual interference factors present challenges, but their combination creates complexity that exceeds simple addition. Electromagnetic interference can affect temperature sensors, creating cascading errors in climate monitoring systems. Chemical pollutants become more toxic under thermal stress. Acoustic interference combines with light pollution to create hostile urban environments for wildlife.

This convergence particularly affects technological systems designed for environmental monitoring and management. Satellite observations can be corrupted by atmospheric interference, ground-based sensors face electromagnetic and chemical interference, and data transmission systems must contend with signal degradation from multiple sources. As we increasingly rely on environmental monitoring for early warning systems and resource management, understanding and mitigating these interference patterns becomes critical.

Biological Adaptation and Evolutionary Responses

Nature doesn’t passively accept interference—organisms adapt, evolve, and sometimes thrive in disrupted environments. Urban birds have evolved shorter, higher-pitched songs that cut through traffic noise. Some fish populations show resistance to chemical pollutants after decades of exposure. Insects adapt to artificial light, with some species now preferring lit environments.

However, adaptation carries costs. Energy diverted to coping with interference factors becomes unavailable for growth, reproduction, or immune function. Populations that successfully adapt to urban interference may lose genetic diversity, reducing their capacity to respond to future challenges. And adaptation timescales matter—while some species evolve rapidly, others cannot keep pace with anthropogenic change rates, leading to population declines or local extinctions.

Monitoring and Mitigation: Tools for Managing Interference 📊

Addressing environmental interference requires first detecting and quantifying these hidden disruptors. Modern sensor networks, satellite observations, and citizen science initiatives create unprecedented opportunities for interference monitoring. Internet of Things (IoT) devices deployed across landscapes can track electromagnetic fields, chemical concentrations, noise levels, and thermal patterns in real-time, creating detailed maps of interference hotspots.

Machine learning algorithms analyze these data streams, identifying patterns humans might miss and predicting where interference effects will emerge before they become critical. This predictive capacity enables proactive rather than reactive management, preventing interference cascades before they develop.

Practical Mitigation Strategies

Effective interference mitigation operates at multiple scales. At individual levels, choices about technology use, lighting, and chemical products reduce personal interference footprints. Communities can implement dark sky ordinances, noise regulations, and electromagnetic zoning. Industries increasingly adopt cleaner production methods, waste heat recovery systems, and interference-aware facility design.

Green infrastructure provides nature-based mitigation solutions. Urban forests absorb sound, moderate temperatures, and filter chemical pollutants. Wetlands process agricultural runoff, removing excess nutrients and chemical contaminants. Ecological corridors allow wildlife to navigate around interference hotspots, maintaining population connectivity despite environmental disruption.

Future Trajectories: Interference in an Uncertain World 🔮

Climate change amplifies many interference factors while introducing new complications. Rising temperatures increase the volatility of chemical pollutants, alter acoustic propagation properties, and stress organisms already coping with multiple disruptions. Extreme weather events create pulse disturbances that interact unpredictably with chronic interference factors.

Emerging technologies present both opportunities and challenges. 5G networks increase electromagnetic field density while enabling better interference monitoring. Artificial intelligence can optimize systems to minimize interference but requires energy-intensive computing infrastructure. Biotechnology offers pollution remediation solutions but introduces novel organisms into ecosystems with uncertain interference potential.

The expansion of human activities into previously pristine environments—deep oceans, polar regions, outer space—extends interference factors into the last relatively undisturbed areas. These frontiers face interference patterns before we fully understand their baseline conditions, creating challenges for establishing meaningful conservation targets.

Building Interference-Aware Futures

Creating sustainable futures requires embedding interference awareness into decision-making across all sectors. Urban planning must consider not only buildings and infrastructure but also their electromagnetic, acoustic, thermal, and light footprints. Agricultural systems need designs that minimize chemical interference while maintaining productivity. Energy systems should account for their full interference profiles, not just carbon emissions.

Education plays a crucial role in this transformation. Most people remain unaware of how their activities generate interference or how they’re affected by environmental disruptions. Integrating interference concepts into environmental literacy helps individuals make informed choices and supports collective action for mitigation.

Policy frameworks increasingly recognize interference factors. Environmental impact assessments now commonly address noise and light pollution alongside traditional concerns. Some jurisdictions implement “right to dark sky” protections or establish electromagnetic exposure limits. However, gaps remain—particularly for emerging interference types and cumulative effects across multiple factors.

The Path Forward: Integration and Action 🌱

Environmental interference factors will continue shaping our world whether we acknowledge them or not. The critical question is whether we’ll manage these disruptions intentionally or allow them to accumulate until system-wide failures force reactive responses. Evidence suggests proactive interference management delivers multiple co-benefits: reduced energy consumption, improved public health, enhanced ecosystem services, and increased system resilience.

Success requires interdisciplinary collaboration spanning natural sciences, engineering, social sciences, and humanities. Technologists must design interference-minimizing systems. Ecologists need to understand how organisms respond to multiple stressors. Social scientists should explore how communities perceive and value interference mitigation. Policymakers must translate scientific understanding into effective regulations.

Individual actions matter too. Reducing unnecessary electromagnetic emissions, choosing products with lower chemical footprints, supporting dark sky initiatives, and advocating for comprehensive environmental policies all contribute to interference mitigation. Collectively, these choices reshape markets, influence regulations, and demonstrate public demand for interference-aware development.

The hidden disruptors shaping our world operate beneath awareness but not beyond influence. By unveiling these interference factors, understanding their mechanisms, and implementing thoughtful mitigation strategies, we can create futures where human activities and natural systems coexist with reduced conflict. The challenges are substantial, but so are the opportunities—for innovation, restoration, and reimagining our relationship with the environment that sustains us all.

As we move forward into an increasingly complex and interconnected future, our ability to recognize, monitor, and manage environmental interference factors will largely determine whether we successfully navigate the challenges ahead or stumble through avoidable crises. The choice, ultimately, rests with us. 🌏

Toni Santos is a health systems analyst and methodological researcher specializing in the study of diagnostic precision, evidence synthesis protocols, and the structural delays embedded in public health infrastructure. Through an interdisciplinary and data-focused lens, Toni investigates how scientific evidence is measured, interpreted, and translated into policy — across institutions, funding cycles, and consensus-building processes. His work is grounded in a fascination with measurement not only as technical capacity, but as carriers of hidden assumptions. From unvalidated diagnostic thresholds to consensus gaps and resource allocation bias, Toni uncovers the structural and systemic barriers through which evidence struggles to influence health outcomes at scale. With a background in epidemiological methods and health policy analysis, Toni blends quantitative critique with institutional research to reveal how uncertainty is managed, consensus is delayed, and funding priorities encode scientific direction. As the creative mind behind Trivexono, Toni curates methodological analyses, evidence synthesis critiques, and policy interpretations that illuminate the systemic tensions between research production, medical agreement, and public health implementation. His work is a tribute to: The invisible constraints of Measurement Limitations in Diagnostics The slow mechanisms of Medical Consensus Formation and Delay The structural inertia of Public Health Adoption Delays The directional influence of Research Funding Patterns and Priorities Whether you're a health researcher, policy analyst, or curious observer of how science becomes practice, Toni invites you to explore the hidden mechanisms of evidence translation — one study, one guideline, one decision at a time.