Data resolution defines how finely we can measure, observe, and interpret information across every scientific and technological domain we engage with today.

🔍 The Foundation: What Data Resolution Really Means

When we talk about data resolution, we’re essentially discussing the level of detail captured in any measurement or observation. Think of it like the difference between viewing a photograph at thumbnail size versus examining it at full resolution—the information exists in both versions, but clarity varies dramatically. In scientific and technical contexts, resolution determines whether we can distinguish between two closely spaced objects, events, or values.

Resolution manifests differently across various domains. In digital imaging, it’s measured in pixels or dots per inch. In temporal measurements, it refers to how precisely we can pinpoint when something occurred. In spatial contexts, it defines the smallest discernible distance between two points. Each domain has its unique constraints and possibilities.

The pursuit of higher resolution has driven countless technological advances throughout history. From Galileo’s telescopes revealing Jupiter’s moons to modern electron microscopes visualizing individual atoms, pushing resolution boundaries has consistently unlocked new realms of understanding. But this journey isn’t without fundamental limits imposed by physics, technology, and mathematics.

Physical Barriers That Define Our Observational Limits

Nature itself imposes certain non-negotiable boundaries on how precisely we can measure phenomena. The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle stands as perhaps the most famous example, establishing that we cannot simultaneously know both the exact position and momentum of a particle with infinite precision. This isn’t a limitation of our instruments—it’s a fundamental property of reality.

In optical systems, the diffraction limit represents another physical constraint. Light waves naturally spread out as they pass through apertures, creating a fundamental cap on how sharply optical instruments can focus. This limit, roughly half the wavelength of light being observed, explains why conventional light microscopes cannot resolve features smaller than approximately 200 nanometers.

Thermal noise presents yet another boundary. At any temperature above absolute zero, atoms vibrate randomly, introducing unavoidable fluctuations into sensitive measurements. This thermal jitter places practical limits on sensor precision across everything from scientific instruments to consumer electronics.

The Quantum Realm and Measurement Precision

As measurements become increasingly sensitive, quantum effects emerge to complicate the picture. Quantum shot noise, arising from the particle nature of light and matter, sets fundamental limits on signal-to-noise ratios. Even perfectly engineered instruments cannot escape this reality—it’s encoded in the fabric of quantum mechanics.

These quantum constraints become particularly relevant in cutting-edge applications like gravitational wave detection, where instruments must measure distances changing by fractions of a proton’s diameter. Engineers working on these systems must employ ingenious techniques to approach but never quite reach theoretical quantum limits.

💻 Digital Resolution: The Discrete Nature of Modern Data

Modern data collection predominantly occurs through digital sensors and instruments, which introduce a fundamentally different type of resolution limit. Unlike analog measurements that can theoretically vary continuously, digital systems must round observations to discrete values determined by bit depth and sampling rates.

Consider digital audio recording. A CD samples sound at 44,100 times per second with 16-bit resolution, creating 65,536 possible amplitude values. This provides sufficient resolution for human hearing, but represents only a tiny fraction of what’s physically possible. Studio recordings often use 24-bit depth and higher sampling rates, not necessarily because humans can hear the difference, but because it provides headroom for processing and prevents accumulated rounding errors.

The Shannon-Nyquist sampling theorem establishes that to accurately capture a signal, you must sample at least twice the rate of the highest frequency present. This mathematical principle governs everything from audio recording to medical imaging, defining minimum resolution requirements for faithful signal reproduction.

Balancing Resolution Against Practical Constraints

Higher resolution always comes with costs. Storage requirements scale with resolution—doubling image resolution quadruples file size. Processing time increases correspondingly. Bandwidth requirements multiply. Energy consumption rises. These practical considerations force real-world systems to balance resolution against feasibility.

In satellite imaging, operators constantly navigate these tradeoffs. Higher resolution enables more detailed observations but covers smaller areas and requires more transmission bandwidth. Different applications demand different balances—tracking large-scale weather patterns versus identifying individual vehicles requires vastly different resolution approaches.

🔬 Breakthrough Technologies Pushing Resolution Boundaries

Despite fundamental limits, researchers continually develop innovative approaches to extract more information from observations. Super-resolution techniques represent one fascinating category of such advances, using clever mathematics and physics to exceed traditional constraints.

In microscopy, techniques like STED (Stimulated Emission Depletion) and PALM (Photoactivated Localization Microscopy) have achieved resolutions far beyond the diffraction limit. These methods earned their developers the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. They work by exploiting fluorescent molecules’ properties rather than fighting diffraction directly—a perfect example of creative problem-solving around fundamental limits.

Computational photography has revolutionized imaging in consumer devices. Modern smartphones combine multiple exposures, use AI-driven enhancement, and employ computational techniques to produce images that exceed what their tiny lenses should physically allow. These approaches trade computational power for optical quality, making stunning photography accessible in pocket-sized devices.

Machine Learning’s Role in Resolution Enhancement

Artificial intelligence has opened remarkable new possibilities for resolution enhancement. Neural networks trained on millions of images can intelligently interpolate missing details, effectively increasing resolution beyond what sensors directly capture. This isn’t magic—the networks learn patterns about how high-resolution detail typically relates to low-resolution structure.

Medical imaging has particularly benefited from these advances. AI algorithms can reduce scan times while maintaining diagnostic quality, minimizing patient radiation exposure. They can enhance older, lower-resolution archive images to extract additional diagnostic value. However, practitioners must remain cautious about introduced artifacts or hallucinated details that might mislead interpretation.

📊 Resolution in Data Analytics and Information Systems

Resolution concerns extend beyond physical measurements into abstract data domains. In business analytics, temporal resolution determines how finely you can track changes—daily sales figures versus hourly versus real-time. Higher temporal resolution reveals patterns invisible at coarser scales but generates vastly more data to process and store.

Geographic information systems face similar considerations. A global dataset might use kilometer-scale resolution for computational tractability, while city planning requires meter or sub-meter precision. The appropriate resolution depends entirely on the questions being asked and decisions being made.

Database designers must consider what level of detail to preserve. Recording timestamps to the microsecond provides precision but might be overkill for applications where minute-level accuracy suffices. These architectural decisions have lasting implications for system performance and storage costs.

The Challenge of Temporal Resolution in Dynamic Systems

Fast-changing phenomena present particular resolution challenges. Financial markets execute thousands of trades per second—meaningful analysis requires microsecond-scale resolution. Climate systems evolve over decades—useful models must span centuries while maintaining seasonal detail. Each context demands tailored approaches to temporal resolution.

Event detection systems must balance sensitivity against false alarms. Too coarse resolution and you miss critical events. Too fine and you drown in noise or burn through computational resources on insignificant fluctuations. Finding optimal resolution often requires domain expertise and iterative refinement.

🌐 Resolution Considerations Across Scientific Disciplines

Different scientific fields encounter unique resolution challenges shaped by their subjects of study. Astronomy seeks to resolve ever-more-distant objects, pushing against fundamental limits imposed by Earth’s atmosphere and telescope size. Interferometry techniques combine signals from multiple telescopes to create effective apertures spanning continents, achieving resolutions impossible with single instruments.

Neuroscience requires spatial resolution fine enough to distinguish individual neurons while maintaining temporal resolution sufficient to track neural signaling that occurs in milliseconds. Advanced techniques like two-photon microscopy enable researchers to image deep into living brain tissue with subcellular resolution, opening windows into neural dynamics previously inaccessible.

Particle physics operates at the absolute frontier of resolution, probing distances billions of times smaller than atoms. The Large Hadron Collider resolves interactions occurring at length scales around 10⁻¹⁹ meters—distances where our very concepts of space and time may break down. These experiments represent humanity’s finest-resolution observations of physical reality.

Genomics and Molecular Resolution

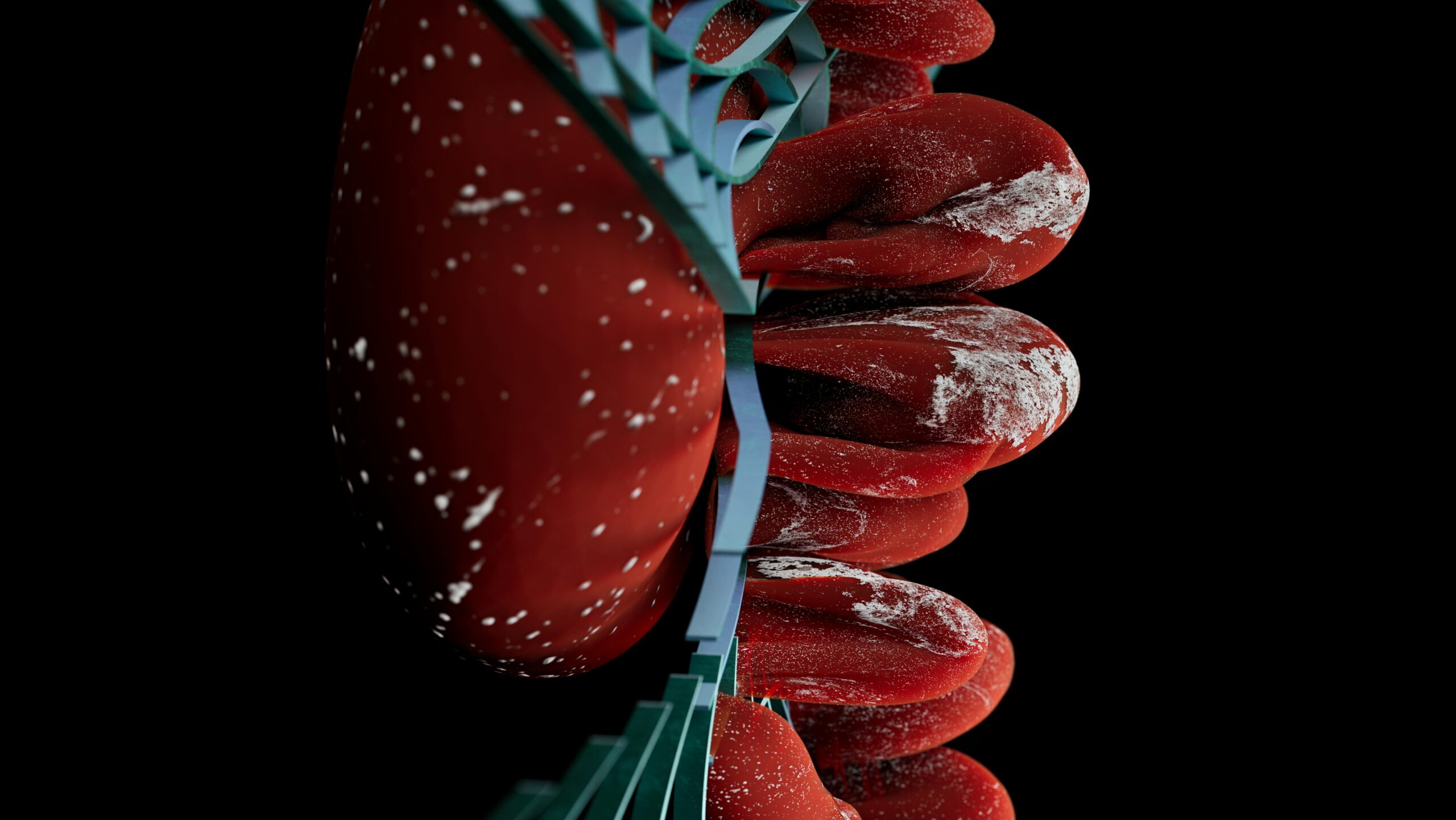

Modern genomics has achieved remarkable molecular resolution, sequencing entire genomes nucleotide by nucleotide. This single-molecule precision has revolutionized biology and medicine, enabling personalized treatments based on individual genetic profiles. Yet even here, higher resolution beckons—epigenetic modifications, three-dimensional chromosome structure, and dynamic molecular interactions demand ever-more-sophisticated observational techniques.

Cryo-electron microscopy now resolves protein structures at near-atomic resolution, earning its developers the 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. This technology has accelerated drug development and deepened our understanding of molecular machinery that drives life itself. The resolution race continues as researchers pursue techniques to observe these molecules in action rather than frozen states.

⚡ Real-Time Systems and the Speed-Resolution Tradeoff

Applications requiring real-time responsiveness face particularly acute resolution tradeoffs. Autonomous vehicles must process sensor data fast enough to react to sudden hazards—higher resolution improves detection but slows processing. Engineers must carefully tune resolution to achieve adequate detail while maintaining reaction speeds that ensure safety.

Medical monitoring systems face similar constraints. Continuous patient monitoring generates enormous data streams. Algorithms must extract clinically significant signals in real-time without overwhelming caregivers with false alarms. Too little resolution and critical changes go undetected. Too much and alarm fatigue diminishes system effectiveness.

Industrial control systems operate under strict timing requirements where missing deadlines can have catastrophic consequences. Sensor resolution must provide sufficient information for accurate control while maintaining deterministic response times. These systems exemplify how resolution requirements emerge from application context rather than pure technical capabilities.

🎯 Choosing Appropriate Resolution for Your Application

Determining optimal resolution requires understanding your specific needs and constraints. Begin by identifying the smallest features or changes that matter for your application. This defines minimum resolution requirements. Then consider practical factors—budget, storage capacity, processing power, and time constraints—that might prevent achieving theoretical ideals.

Avoid the trap of assuming maximum resolution always improves results. Excessive resolution can actually degrade outcomes by amplifying noise, overwhelming analysis systems, or introducing irrelevant detail that obscures meaningful patterns. The best resolution balances information gain against practical costs.

Consider future needs when making resolution decisions. While you shouldn’t pay for unnecessary precision today, ensuring some headroom prevents costly system redesigns later. Modular architectures that allow resolution upgrades as needs evolve provide valuable flexibility without overcommitting resources initially.

Testing and Validation Strategies

Empirical testing provides invaluable insights into resolution requirements. Collect data at multiple resolutions and evaluate how results change. Often you’ll discover that beyond a certain point, additional resolution provides diminishing returns. This sweet spot represents optimal efficiency—adequate detail without wasteful overhead.

Conduct sensitivity analyses to understand how resolution affects downstream decisions or conclusions. In some applications, coarse resolution proves entirely adequate because decision thresholds remain far from resolution limits. In others, seemingly minor resolution differences significantly impact outcomes. Only testing with realistic use cases reveals these relationships.

🚀 The Future Landscape of Data Resolution

Emerging technologies promise continued resolution advances across multiple fronts. Quantum sensors exploit quantum entanglement and superposition to achieve measurement sensitivities approaching fundamental limits. These devices will enable observations currently impossible, from detecting gravitational waves from the universe’s earliest moments to mapping brain activity with unprecedented detail.

Advances in materials science are producing sensors with better performance characteristics—lower noise, faster response, greater dynamic range. Graphene-based sensors, for instance, show promise for applications ranging from medical diagnostics to environmental monitoring, offering sensitivity improvements of orders of magnitude over current technologies.

The fusion of multiple measurement modalities creates opportunities for resolution enhancement through data fusion. Combining lower-resolution but information-rich measurements from different sensors can yield insights impossible from any single source. This multimodal approach increasingly defines state-of-the-art observational systems.

Artificial Intelligence as Resolution Multiplier

As AI capabilities advance, we’ll see increasing use of learned models to extract maximum information from limited-resolution observations. These systems won’t violate physical limits, but they’ll approach those limits more closely by intelligently exploiting statistical patterns and domain knowledge. The boundary between direct measurement and informed inference will continue blurring.

However, this progress requires vigilance. AI-enhanced resolution risks introducing subtle biases or artifacts that could mislead interpretation. Validation frameworks must evolve alongside these technologies to ensure that pursuit of resolution doesn’t compromise measurement integrity or scientific rigor.

🎓 Practical Wisdom for Resolution Decision-Making

Understanding resolution limits empowers better decisions across scientific, technical, and business contexts. Recognize that resolution represents one factor among many determining system effectiveness. Sometimes improving other aspects—noise reduction, calibration accuracy, or analysis methodology—provides greater benefits than resolution increases.

Document your resolution requirements and rationale clearly. Future users will need to understand what your measurements can and cannot reveal. This documentation prevents misinterpretation and helps others determine whether your data suits their purposes or requires collection at different resolution.

Stay informed about advancing capabilities in your domain. Resolution boundaries that seemed immovable five years ago may have fallen to new techniques. Regular reassessment ensures you’re leveraging current capabilities rather than designing around obsolete limitations.

The quest for greater resolution fundamentally drives human understanding forward. Each advance reveals previously hidden details, raises new questions, and expands the frontier of knowledge. While physical and practical limits constrain our observations, human ingenuity continually finds ways to extract more clarity from nature’s signals. Whether you’re designing measurement systems, analyzing data, or simply making informed decisions about technology, understanding resolution—its possibilities, limits, and tradeoffs—provides essential foundation for navigating our increasingly data-driven world. The boundaries of precision continue expanding, promising ever-sharper views of reality’s magnificent complexity.

Toni Santos is a health systems analyst and methodological researcher specializing in the study of diagnostic precision, evidence synthesis protocols, and the structural delays embedded in public health infrastructure. Through an interdisciplinary and data-focused lens, Toni investigates how scientific evidence is measured, interpreted, and translated into policy — across institutions, funding cycles, and consensus-building processes. His work is grounded in a fascination with measurement not only as technical capacity, but as carriers of hidden assumptions. From unvalidated diagnostic thresholds to consensus gaps and resource allocation bias, Toni uncovers the structural and systemic barriers through which evidence struggles to influence health outcomes at scale. With a background in epidemiological methods and health policy analysis, Toni blends quantitative critique with institutional research to reveal how uncertainty is managed, consensus is delayed, and funding priorities encode scientific direction. As the creative mind behind Trivexono, Toni curates methodological analyses, evidence synthesis critiques, and policy interpretations that illuminate the systemic tensions between research production, medical agreement, and public health implementation. His work is a tribute to: The invisible constraints of Measurement Limitations in Diagnostics The slow mechanisms of Medical Consensus Formation and Delay The structural inertia of Public Health Adoption Delays The directional influence of Research Funding Patterns and Priorities Whether you're a health researcher, policy analyst, or curious observer of how science becomes practice, Toni invites you to explore the hidden mechanisms of evidence translation — one study, one guideline, one decision at a time.