Measurement error accumulation silently undermines scientific experiments, engineering projects, and business analytics, transforming seemingly minor inaccuracies into significant distortions that compromise decision-making and outcomes.

🎯 The Hidden Cost of Cumulative Measurement Errors

Every measurement carries inherent uncertainty. Whether you’re tracking temperature in a laboratory, measuring distances in construction, or analyzing customer data in marketing campaigns, small errors compound over time and across multiple measurement points. This phenomenon, known as measurement error accumulation, represents one of the most underestimated challenges in data-driven decision-making.

Understanding how these errors propagate through systems is crucial for professionals across industries. A 0.1% deviation in initial measurements might seem negligible, but after a series of calculations or repeated measurements, this tiny variance can snowball into substantial inaccuracies that invalidate entire datasets or lead to costly mistakes.

Organizations investing millions in analytics infrastructure often overlook the fundamental issue: garbage in, garbage out. Without addressing measurement error accumulation at its source, even the most sophisticated algorithms and powerful computing systems will produce unreliable results.

Understanding the Mechanics of Error Propagation

Measurement errors typically fall into two categories: systematic errors and random errors. Systematic errors stem from consistent biases in measurement instruments or methodologies, while random errors arise from unpredictable fluctuations in measurement conditions. Both types accumulate, but through different mechanisms.

Systematic errors compound additively when measurements are repeated or used in sequential calculations. If your scale consistently reads 2 grams heavy, ten measurements will introduce a cumulative error of 20 grams. This predictability makes systematic errors easier to identify and correct once detected.

Random errors, conversely, accumulate according to statistical principles. They don’t simply add up linearly; instead, their combined effect follows the square root of the number of measurements. This statistical behavior means that while random errors do accumulate, they do so more slowly than systematic ones, providing some natural mitigation.

The Mathematics Behind Error Accumulation

When combining measurements through addition or subtraction, absolute errors add up. If measurement A has an uncertainty of ±2 units and measurement B has ±3 units, their sum carries an uncertainty of approximately ±3.6 units (calculated as the square root of 2² + 3²).

For multiplication and division operations, relative errors combine. A 5% error in one measurement multiplied by another measurement with 3% error results in approximately 5.8% relative error in the product. These mathematical relationships demonstrate why error accumulation accelerates in complex calculations involving multiple steps.

🔬 Industry-Specific Challenges and Consequences

Manufacturing and quality control operations face particularly acute challenges with measurement error accumulation. Production lines taking thousands of measurements daily must maintain tight tolerances, yet each inspection point introduces potential inaccuracy. A pharmaceutical company measuring active ingredient concentrations cannot afford accumulated errors that might push batches outside regulatory compliance ranges.

In financial modeling, measurement errors in input variables propagate through complex algorithms, potentially miscalculating risk exposures or investment returns. A hedge fund relying on accumulated historical price data with measurement inconsistencies might construct fundamentally flawed trading strategies, exposing investors to unexpected losses.

Healthcare diagnostics represent another critical domain where measurement accuracy directly impacts patient outcomes. Medical imaging equipment, laboratory test instruments, and vital sign monitors must minimize error accumulation. A blood glucose monitor with slight calibration drift could lead diabetic patients to make inappropriate insulin dosing decisions over time.

Environmental Science and Climate Modeling

Climate scientists collect temperature, precipitation, and atmospheric composition data from thousands of monitoring stations globally. Small calibration differences between instruments, combined with data collection spanning decades, create significant challenges in detecting genuine climate signals amid measurement noise. Researchers must employ sophisticated statistical techniques to separate real environmental changes from accumulated measurement artifacts.

Identifying Sources of Measurement Uncertainty

The first step toward controlling error accumulation involves identifying where uncertainties enter your measurement system. Common sources include instrument precision limits, environmental factors affecting measurements, human error in reading or recording values, and data processing or transmission errors.

Instrument precision represents the resolution limit of your measurement tools. A ruler marked in millimeters cannot accurately measure submillimeter dimensions. Digital instruments introduce quantization errors when converting continuous physical quantities into discrete numerical values. These limitations establish a floor for achievable accuracy regardless of measurement technique.

Environmental conditions significantly impact measurement stability. Temperature fluctuations cause materials to expand or contract, affecting dimensional measurements. Humidity influences electronic sensors. Vibrations introduce noise into sensitive equipment. Controlling these environmental variables reduces one major contributor to accumulated uncertainty.

Human Factors in Measurement Error

Despite automation advances, human involvement remains common in data collection workflows. Parallax errors when reading analog gauges, transcription mistakes when recording values, and inconsistent measurement techniques between operators all inject variability. Training standardization and automated data capture systems minimize these human-originated errors.

🛠️ Practical Strategies for Error Minimization

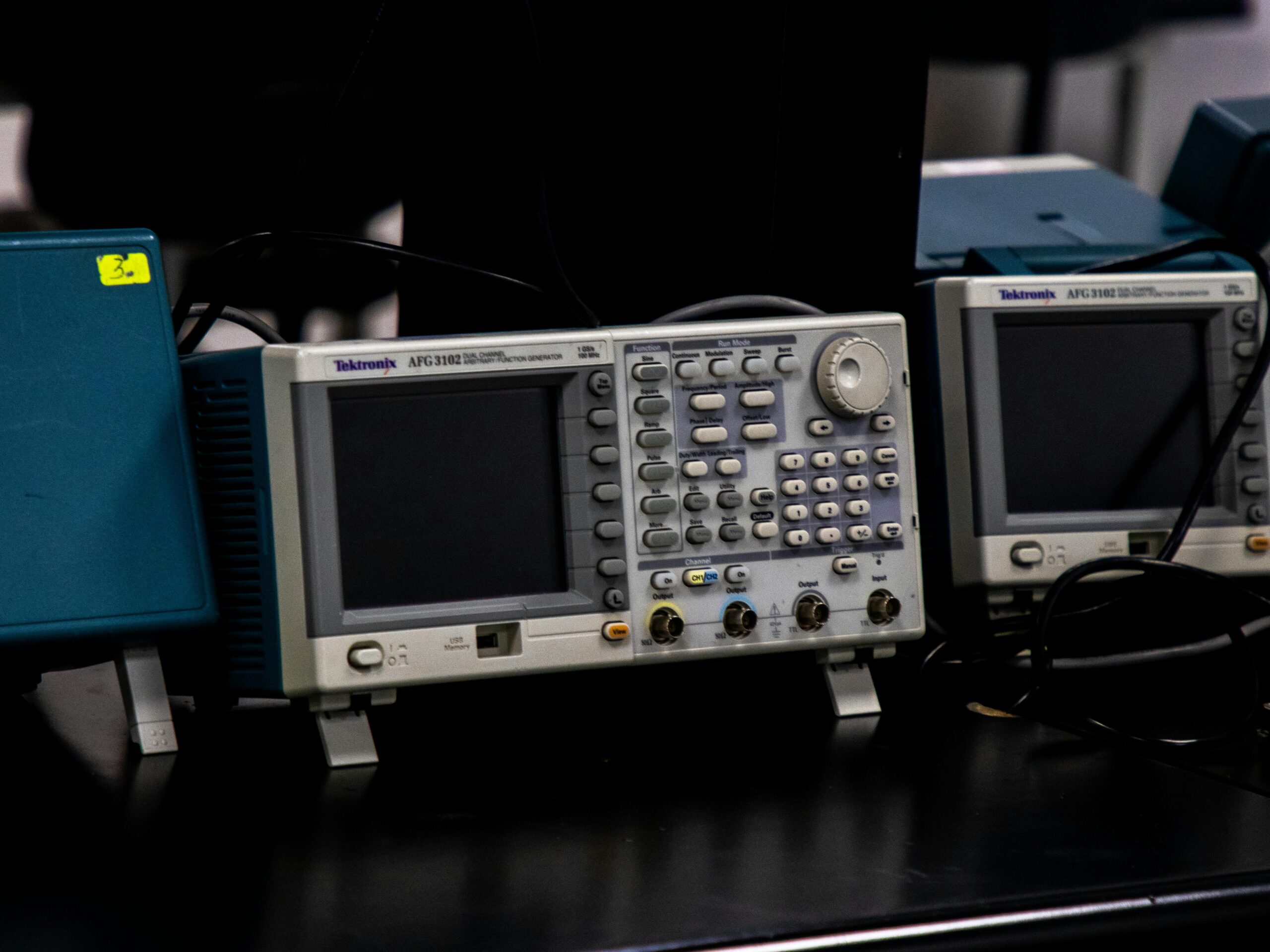

Calibration represents your first line of defense against systematic error accumulation. Regular calibration against known reference standards detects and corrects instrument drift before it significantly impacts results. Establishing calibration schedules based on instrument stability characteristics ensures measurements remain within acceptable accuracy bounds.

Implementing measurement redundancy provides powerful error detection capabilities. Taking multiple measurements with different instruments or methods allows statistical comparison to identify outliers and reduce random error through averaging. This approach, while resource-intensive, proves essential for high-stakes measurements where accuracy justifies the additional effort.

Statistical process control techniques borrowed from manufacturing quality management help monitor measurement systems for emerging problems. Control charts tracking measurement repeatability and reproducibility reveal when instruments drift outside normal operating parameters, triggering investigation before errors accumulate to problematic levels.

Leveraging Technology for Precision

Modern sensor technology increasingly incorporates built-in error correction algorithms. Smart sensors with self-calibration capabilities automatically compensate for temperature effects, aging drift, and other systematic error sources. While more expensive than traditional instruments, these intelligent devices significantly reduce maintenance burden and improve long-term accuracy.

Digital data acquisition systems eliminate transcription errors inherent in manual data recording. Direct computer interface from measurement instruments to analytical software removes human intermediaries who might introduce mistakes. These systems also maintain complete audit trails, supporting error investigation when anomalies appear.

Statistical Techniques for Error Quantification

Understanding the magnitude of accumulated uncertainty requires rigorous statistical analysis. Uncertainty budgeting systematically accounts for all error sources contributing to a measurement result, combining them according to established mathematical rules to estimate total uncertainty.

Monte Carlo simulation offers a powerful computational approach for complex measurement scenarios. By randomly varying input parameters within their uncertainty ranges and observing how output values distribute, analysts can quantify how errors propagate through elaborate calculations that defy analytical solutions.

Bayesian inference provides sophisticated frameworks for updating uncertainty estimates as additional information becomes available. This approach proves particularly valuable when combining measurements from different sources with varying reliability, weighting each contribution appropriately in the final result.

Confidence Intervals and Reporting Standards

Properly communicating measurement uncertainty matters as much as calculating it correctly. Reporting results with confidence intervals explicitly acknowledges inherent limitations while providing recipients with necessary context for interpretation. A measurement stated as “15.7 ± 0.3 meters at 95% confidence” conveys far more useful information than simply “15.7 meters.”

International standards organizations have developed comprehensive guidelines for expressing measurement uncertainty. The Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) provides a standardized framework adopted across scientific and industrial communities, ensuring consistent uncertainty communication regardless of measurement domain.

📊 Designing Robust Measurement Protocols

Thoughtful measurement protocol design proactively prevents error accumulation rather than merely detecting it after the fact. Starting with clear measurement objectives, protocols should specify required accuracy levels, acceptable uncertainty ranges, and validation procedures ensuring these targets are met.

Minimizing measurement steps reduces opportunities for error introduction. Each additional manipulation, calculation, or data transfer potentially injects new uncertainty. Simplifying workflows to the essential minimum while maintaining necessary rigor keeps cumulative errors under control.

Building in periodic verification checkpoints throughout extended measurement campaigns catches developing problems early. Measuring known reference standards alongside unknown samples provides ongoing quality assurance, confirming the measurement system continues operating within specifications.

Documentation and Traceability Requirements

Comprehensive documentation enables retrospective error analysis when unexpected results emerge. Recording instrument identifications, calibration dates, environmental conditions, operator identities, and measurement procedures creates an audit trail supporting investigation. This traceability proves particularly critical in regulated industries where measurement validity must be defensible.

🚀 Advanced Approaches for Critical Applications

High-stakes applications demanding exceptional accuracy justify sophisticated error reduction techniques beyond standard practices. Differential measurement approaches compare unknowns against nearby reference standards rather than absolute measurement scales, canceling many systematic errors affecting both measurements similarly.

Heterodyne and nulling techniques in metrology eliminate direct measurement entirely, instead balancing unknown quantities against adjustable references until detecting no difference. This approach transfers measurement accuracy requirements from absolute measurement to precise null detection, often achieving superior results.

Algorithmic error correction applies mathematical transformations compensating for known measurement system characteristics. When instrument response functions are well-characterized, computational deconvolution can partially reverse distortions introduced during measurement, recovering more accurate estimates of true underlying values.

Machine Learning for Error Prediction

Artificial intelligence algorithms trained on historical measurement data can learn patterns in how errors develop over time. Predictive models forecast when instruments will drift outside specifications, enabling proactive maintenance. Anomaly detection algorithms automatically flag suspect measurements deviating from expected patterns, preventing corrupted data from contaminating analyses.

Building an Organizational Culture of Measurement Quality

Technical solutions alone cannot solve measurement error accumulation. Organizational culture significantly influences whether error minimization receives adequate attention and resources. Leadership must prioritize measurement quality, allocating budgets for proper equipment, training, and quality assurance processes.

Creating clear accountability for measurement accuracy ensures someone specifically owns this responsibility rather than assuming everyone collectively maintains quality. Designated metrology specialists or quality assurance personnel bring focused expertise and establish consistent standards across measurement activities.

Continuous improvement programs systematically reduce error sources over time. Regular reviews of measurement performance, root cause investigations of identified problems, and implementation of corrective actions gradually enhance measurement system capabilities. Celebrating improvements reinforces cultural emphasis on quality.

💡 The Path Forward: Sustainable Measurement Excellence

Achieving reliable results despite measurement error accumulation requires ongoing commitment rather than one-time interventions. As measurement requirements evolve and new technologies emerge, organizations must continuously reassess their approaches to maintain accuracy in changing contexts.

Investing in measurement infrastructure pays long-term dividends through improved decision quality, reduced waste, enhanced customer satisfaction, and regulatory compliance. While quality measurement systems require upfront resources, the costs of poor measurement—failed products, misguided strategies, and lost credibility—far exceed prevention investments.

The measurement challenges you face today will evolve tomorrow. Building flexible, adaptable measurement frameworks positions your organization to maintain accuracy as requirements change. Cultivating in-house expertise, staying current with evolving best practices, and maintaining relationships with metrology communities ensures continued access to knowledge needed for measurement excellence.

Precision measurement represents more than technical capability—it embodies an organizational commitment to truth and reliability. Every data point you collect either builds or erodes trust in your conclusions. By systematically addressing measurement error accumulation, you unlock the accurate insights and dependable results that drive success in an increasingly data-dependent world.

Toni Santos is a health systems analyst and methodological researcher specializing in the study of diagnostic precision, evidence synthesis protocols, and the structural delays embedded in public health infrastructure. Through an interdisciplinary and data-focused lens, Toni investigates how scientific evidence is measured, interpreted, and translated into policy — across institutions, funding cycles, and consensus-building processes. His work is grounded in a fascination with measurement not only as technical capacity, but as carriers of hidden assumptions. From unvalidated diagnostic thresholds to consensus gaps and resource allocation bias, Toni uncovers the structural and systemic barriers through which evidence struggles to influence health outcomes at scale. With a background in epidemiological methods and health policy analysis, Toni blends quantitative critique with institutional research to reveal how uncertainty is managed, consensus is delayed, and funding priorities encode scientific direction. As the creative mind behind Trivexono, Toni curates methodological analyses, evidence synthesis critiques, and policy interpretations that illuminate the systemic tensions between research production, medical agreement, and public health implementation. His work is a tribute to: The invisible constraints of Measurement Limitations in Diagnostics The slow mechanisms of Medical Consensus Formation and Delay The structural inertia of Public Health Adoption Delays The directional influence of Research Funding Patterns and Priorities Whether you're a health researcher, policy analyst, or curious observer of how science becomes practice, Toni invites you to explore the hidden mechanisms of evidence translation — one study, one guideline, one decision at a time.